Happy Monday, dear readers!

Your humble blogger is back for the moment, and brings you the rather bitter-sweet story of the case of Padilla v. Rio Farms LLC.

Now, other than “take nothing,” there is no sweeter sound emanating from a workers’ compensation file than “C&R.” The thought of wrapping up all issues and washing your hands of a case is exhilarating. And, of course, it lets us all focus on the real reason we got into workers’ compensation – lien resolution!

But the Order Approving C&R was just the start of the headaches in the Padilla case, rather than the end of them.

The parties reached a C&R agreement for the sum of $42,500, out of which EDD was to be paid $5,965.71 and the attorney was to be paid $6,375.00, leaving $30,159.29 for the applicant. Although the C&R language provided that defendant would be entitled to credit for permanent disability advances, in the area provided to enter the amount advanced to date, the C&R reflected $0.

In issuing payment, defendant asserted a credit of PD advances in the sum of $11,020 to reduce the total C&R. Applicant objected, claiming he was entitled to the full $30,159.29.

The matter proceeded to trial and the WCJ issued an order rejecting defendant’s claim for credit. The WCAB denied defendant’s petition for reconsideration.

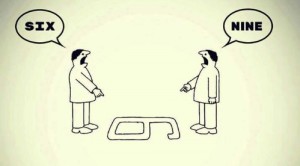

Relying on various provisions of the Civil Code, the WCAB commissioners noted that defendant failed to assert the PDAs to date at the time the C&R was drafted, and went so far as to list advances to date as $0 (rather than leaving the field blank).

This happens a lot, actually – sometimes the benefits printouts are stale, sometimes there is an oversight on the part of the adjuster, the attorney, or both. What’s more, some applicants are looking at a C&R for “new money,” so updated information might have had zero impact in this case, as it does in many other cases: asserting a credit for PDAs in the sum of $11,020 might just drive up the price of a C&R by the same sum.

But here’s the fun part – no one is saying that applicant did NOT receive this money. If he’s got the $11,020, then on what grounds is he keeping it?

In 2014, Prakashpalan v. Engstrom et al, the Court of Appeal defined unjust enrichment as follows: “[t]he theory of unjust enrichment requires one who acquires a benefit which may not justly be retained, to return either the thing or its equivalent to the aggrieved party so as not to be unjustly enriched.” (citing Lectrodryer).

Well, doesn’t the same theory apply here? Either applicant received permanent disability advances or he did not. If he did receive advances, then should defendant receive credit for the moneys paid? If he did not receive advances, then what were the sums he did receive? Should the insurer have a free hand to pursue an unjust enrichment claim in civil court? (The applicant might not have the money by the end of the lawsuit, which is a different story, of course).

In any case, this is a reminder to all of us that we should try to keep the lines of communication between the adjuster desk and the attorney desk as open as possible.

So, dear readers, does the file coming up for hearing have any advances on it? Are you suuuuuuure?

Onward, dear readers, onward!